Reviews—Film and Literature

How did New England Puritans reconcile their faith with the emergence of scientific empiricism? As Sarah Rivett, a literary scholar at Princeton, tells it, they did so with relative ease. Rivett argues that both Puritans and practitioners of the new science grappled with the limitations of humankind’s perceptive faculties. By the middle of the 17th century, the “study of the soul and the study of the world” had emerged as “parallel empirical techniques.” Animated by the essential optimism of John Calvin’s Institutes, Puritan studies of the soul and scientific studies of the world eagerly sought answers for seemingly unknowable questions. Like Charles Webster, a towering figure in the history of science and medicine, Rivett clarifies the often-murky relationship between religion and science in the early modern world. Unlike Webster, Rivett closely considers the place of women and native peoples in that history, as well as the nature of the evidence that “soul” scientists examined.

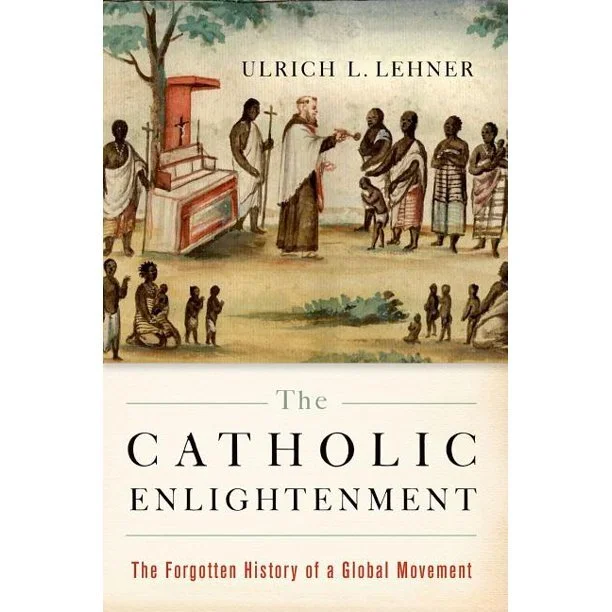

In The Catholic Enlightenment: The Forgotten History of a Global Movement, Ulrich Lehner challenges the longstanding academic assumption that the Enlightenment and Catholicism are fundamentally incompatible. Citing the Council of Trent’s emphasis on a theology of human freedom, Lehner posits that the men he calls “Catholic Enlighteners” were “moderates, favoring a modernization that compromised with tradition and reigning authorities.” These 18th-century Enlighteners had two aims: to use scientific and philosophic achievements to defend Catholicism in a new language, and to reconcile their faith with modern culture. Although Lehner recognizes local variations in the particulars of Enlightened Catholic belief, he suggests that they generally shared a scholastic tradition that disdained religious enthusiasm, and had little room for superstition or prejudice.

Keith Thomas’s Religion and the Decline of Magic: Studies in Popular Beliefs in Sixteenth and Seventeenth Century England is a standard in early modern European history. This wide-ranging study examines both the tensions and the congruences between the established church’s teachings and popular belief.

In the fall of 1843, Charles Dickens walked the empty streets of London late at night wrestling with the question: Are there answers to humanity’s indifference, negligence and lack of charity? Is there solace to be found in a holiday tale? From those solitary walks, sometimes ten to twenty miles at a time, the idea for a story grew and blossomed. Dickens completed A Christmas Carol in six weeks and published it on December 17, 1843. The first edition sold out in three days. A Christmas Carol had touched a nerve. It was an otherworldly remedy for a world-weary age, and an unsettling admonition to those who neglected the poor and destitute. It was his tribute to the “Spirits of Christmas,” and it served as a counterbalance and restorative measure against societal apathy and community disconnect. Dickens did not call for a government solution to poverty, a new program, or a symposium. He asked his readers to change how they interacted with their fellow voyagers, to be a kinder, more generous, and better version of themselves.

Flannery O’Connor was a remarkable 20th-century American writer of startling, strange, and sometimes violent short stories and novels set in the rural South. In the last year of her too-short life, she worked between medical treatments and hospitalization, writing and correcting the last draft of “Revelation,” one of her final short stories. It remains a well-crafted masterpiece, the culmination of all she intended to say about the fallen human condition and the power of grace to pierce through the veil and open your eyes to yourself and those around you.

Few literary commentators would dispute that Wilfred Owen was one of the greatest war poets of the last hundred years. He wrote from personal experience as a British soldier in World War I. Surprisingly, these poems were written in just over a year, and of those he fought with, few knew he had such a gift.

Ernest Hemingway’s book A Moveable Feast was published posthumously in 1964. It is composed of poignant sketches looking back on Hemingway’s time in France with his first wife and their baby Jack, known as Bumby. It is set after World War I, when Hemingway was an unknown, struggling American writer living in poverty above a sawmill, writing in the cafes and roaming the streets of Paris.

Washington Irving’s collection of short stories and essays, The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent, captivated American and European readers. The major American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow said that everyone has a book that fires their imagination and is burned into their psyche well past childhood. For him, it was Washington Irving’s The Sketch Book. The stories are enchanting, haunting, humorous, astonishing and uniquely American. They made Washington Irving into an unexpected star at a relatively young age—37. In his career, he was a determined historian, trusted diplomat, superb essayist, and presidential biographer, but he was and is remembered principally as the writer of The Sketch Book collection, and especially a particular story found within it, “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow.”

John Kaag’s latest work, American Philosophy: A Love Story, masterfully leads readers through a compelling personal narrative intertwined with an introduction to American philosophical thought.

This combination memoir and history begins in the backwoods of New Hampshire. On an escape to a small philosophy conference, Kaag, a philosophy professor at UMass Lowell, stumbles into the decaying library of long-deceased Harvard philosopher William Hocking in the town of Chocorua. Followed by the ghosts of his failing marriage and recently deceased alcoholic father, Kaag throws himself into the depths of the library as the Hocking family struggles to prop up the collapsing estate. In befriending Hocking’s granddaughters, he commits to cataloging the massive library, which is composed of numerous first editions and signed copies from American philosophers ranging from Emerson to Twain to Whitman.

To the average viewer, photography consists of still images, blandly depicting a mere moment. It is easy to gloss over the details within a photograph. This has led viewers, and for a time it led artists and critics, to dismiss photography as an art form. Moreover, in a stimulus-seeking society, what can photography offer that more abstract or traditional media do not already substantially provide?